In the west of Ireland, amidst the rugged, windswept landscapes of County Mayo, lies a vast and often brooding expanse of water known as Loch Mask. This is a place steeped in history and folklore, its stony shores and deep cold waters holding stories that stretch back through the centuries. But one of the most chilling tales it has to tell is a true one, dating back to the bitter winter of 1882.

It is the story of a man named Joseph Huddy, a local bailiff, and his young grandson John. Joseph was a man in his late sixties, a figure of authority in a time when such authority was deeply resented by many of his neighbours. He worked for Lord Ardilaun, a prominent local landlord, and his job was to enforce the landlord's will, a role that made him few friends among the struggling tenant farmers of the region.

Joseph Huddy was not just an official, he was a family man, a grandfather who, on a fateful day in January, was accompanied by his ten-year-old grandson John. Young John was likely just tagging along for the boat journey, an adventure with his grandad across the Loch.

he would have been oblivious to the simmering tensions that his grandfather's work stirred up. For John, it was simply a day out on the water, a chance to see the stark beauty of Lough Masque up close. The Lough itself is a formidable body of water, the second largest in Ireland known for its unpredictable weather and treacherous currents.

Its waters can turn from a calm, glassy mirror to a churning, grey tempest in a matter of minutes, a danger well known to all who lived by its shores. The role of a bailiff in nineteenth-century Ireland was a perilous one. They were the enforcers of the landlord system, responsible for serving eviction notices and legal summonses to tenants who could not pay their rent.

In an era of widespread poverty, crop failures and political agitation for land reform, the bailiff was often seen as the face of an oppressive system. He was the man who knocked on the door with bad news, the agent of a distant and powerful landlord. For Joseph Huddy, this meant he was a marked man in his own community, walking a tightrope between his duty to his employer and the anger of his neighbours. He was a local man, yet his job placed him firmly on the other side of a bitter divide.

This story therefore begins not just with two people, but with the immense social and political pressures that define their lives. It is a tale set against a backdrop of deep-seated conflict, a struggle for land, for rights, and for survival itself. Joseph and John Huddy were about to become central figures in a drama that would horrify the public, expose the raw wounds of Irish society,

and leave a dark stain on the history of Lochmasc. Their journey across the loch was meant to be a routine part of Joseph's duties, but it would descend into a mystery that captured the attention of the entire British Isles, a sombre chapter in the long and often painful story of Ireland. The morning of Tuesday, the 10th of January, 1882, dawned cold and bleak over Lochmasc.

It was on this day that Joseph Huddy and his grandson John set out from the town of Clonburh on what was for Joseph a routine but unpleasant task. He had been instructed to serve legal summonses on several tenants living on the far side of the loch. These tenants had fallen behind on their rent to Lord Adelon, and the summonses were the first step in a legal process that could ultimately lead to their eviction.

To make the journey, Huddy hired a local boatman, a man named Michael Hines, who would ferry them across the vast chilly waters in his boat. The journey itself would have been a long and cold one, taking them to a remote and isolated part of the shoreline. For young John, the trip might have held a sense of adventure, but for his grandfather, it was fraught with tension.

He was travelling into a community that viewed him with suspicion and hostility. The tenants he was to visit were not strangers, they were part of the fabric of the local area, and serving them with these papers was an act that would be seen as a betrayal by many. The land they farmed was, in their eyes, rightfully theirs, and the rents demanded by the distant landlord were a constant source of hardship and resentment.

Huddy knew he was entering a potentially dangerous situation, but it was his job, and in the island of 1882 a steady job was not something to be taken lightly, no matter the risks involved. The party of three, Huddy, his grandson, and the boatman Hines, made their way across the Loch. They successfully landed on the western shore, and Huddy proceeded with his task, delivering the legal papers to the tenants as instructed.

According to later accounts, the process was tense, but concluded without immediate violence. Once the summonses were served, the trio prepared for their return journey. The winter light would have been fading early, and the wind picking up across the water. They pushed their boat back into the loch, with Clonburh and the relative safety of home as their destination. This was the last time any of them were seen alive by people on the shore.

As they rode away from the land, they vanished into the grey expanse of the loch. They became silhouettes against the darkening sky, and then were gone. When they failed to return to Clonba that evening, initial concerns were likely muted. Lochmasc was known for its sudden squalls, and it was possible they had been forced to take shelter on one of the loch's many small islands, waiting for the weather to improve.

But as the night wore on, and the next day dawned with no sign of the boat or its passengers, a sense of unease began to creep through the community. The routine errand had turned into a silent, unnerving disappearance, and the mystery of what happened out on that cold water had begun.

To understand the disappearance of Joseph and John Huddy, we must look beyond the shores of Lochmasc and into the heart of a nationwide crisis that was tearing Ireland apart. This period from roughly 1879 to 1882 is known as the Land War.

It was a time of intense and often violent agitation by Irish tenant farmers against the system of landlordism that had dominated the country for centuries. For generations, the majority of the Irish population were tenants renting small plots of land from a small number of powerful and often absent landlords. These tenants had very few rights, faced the constant threat of eviction, and were subject to rents that could be raised at the landlord's whim.

Following several years of poor harvests and the threat of another famine reminiscent of the Great Hunger of the 1840s, tensions reached a boiling point. An organisation called the Irish National Land League was formed in 1879, led by the charismatic politician Charles Stuart Parnell. The League's aims were simple and summed up in their slogan, The Land of Ireland for the People of Ireland.

They demanded what became known as the three Avis, fair rent, fixity of tenure, meaning tenants could not be evicted if they paid their rent, and free sale, the right of a tenant to sell their interest in their farm. This movement mobilised hundreds of thousands of people across the country in a campaign of resistance against the landlord system.

The Land League's tactics were powerful and effective. They organised mass meetings, encouraged tenants to collectively refuse to pay unjust rents, and supported those who were evicted. One of their most famous tactics was the boycott, a term that actually originated during this period.

It was named after Captain Charles Boycott, a land agent in County Mayo, who became the first target of this new form of social ostracism. When he tried to evict tenants, the local community, under the guidance of the Land League, refused to have any dealings with him. His workers left, shops would not serve him, and he was completely isolated.

This non-violent but devastatingly effective weapon was soon used against landlords, agents and bailiffs across Ireland. This was the world Joseph Huddy inhabited. As a bailiff for Lord Ardilaun, he was on the front line of this conflict. He was the man tasked with enforcing the very laws and practices the Land League was fighting against. In the eyes of his neighbours, he was not just a man doing a job, he was an instrument of their oppression, a collaborator with the enemy.

The summonses he carried in his pocket were not just pieces of paper, they were symbols of a system that kept people in poverty and fear. The anger directed at the landlords was often channeled towards the men who worked for them on the ground. This meant that Huddy's journey was not just a trip across a lake, it was a journey into the heart of a bitter and deeply personal conflict.

When Joseph Huddy, his grandson, and the boatman Michael Hynes did not return to Clonburh, the initial explanation for many was the treacherous nature of Loch Mask itself. The loch is notorious for its sudden violent squalls that can whip up the water into a frenzy, easily capable of swamping a small wooden boat. The idea that they had met with a tragic accident was a plausible and frighteningly common occurrence on the great lakes of the west of Ireland.

People imagined their small craft being overturned by a sudden gust of wind plunging all three into the lethally cold water. In the depths of winter, survival in such conditions would have been measured in minutes, not hours. It was a grim but logical possibility.

However, as the hours turned into days, this simple explanation began to feel insufficient. An accident, however tragic, would likely have left some evidence. A piece of wreckage, an oar, or even the boat itself should have washed up on the loft's extensive shoreline. But there was nothing. The surface of the loft remained stubbornly silent, offering no clues as to the fate of the three missing people.

This complete lack of evidence began to fuel a different and more sinister theory. The silence was too perfect, too absolute. It felt less like the aftermath of a random accident and more like the result of a deliberate calculated act designed to leave no trace. Rumours began to swirl through the local communities, whispered in public houses and around turf fires. Given the intense atmosphere of the land war, suspicion quickly fell upon the tenants Huddy had gone to serve with summonses.

Had they, in their anger and desperation, taken matters into their own hands? The theory went that Huddy and his companions had been ambushed, murdered, and their bodies, along with their boat, carefully weighted down and sunk in the deepest part of the loft. This would explain the lack of any wreckage. It was a horrific thought, but in the context of the times it was not an unbelievable one.

The land war had seen violence before and the hatred for bailiffs was real and palpable. The disappearance became a stark symbol of the divisions within the community. On one side were the authorities, the landlords and those loyal to the Crown, who were increasingly convinced that a foul murder had taken place, a brutal act of agrarian outrage.

On the other side were the tenant farmers and their supporters, who maintained a wall of silence. Some genuinely believed it was an accident, while others, even if they suspected foul play, were unwilling to cooperate with the police, whom they saw as agents of the landlord class. The Loch, which had once been a shared resource for fishing and transport, now seemed like a dark, watery barrier separating two sides of a bitter conflict, holding its terrible secret deep within its cold embrace.

With growing fears of a triple murder, the authorities launched one of the most extensive search operations the west of Ireland had ever seen. The Royal Irish Constabulary, or RIC, the armed police force of the time, took the lead. They began by systematically scouring the entire 20-mile length of Loch Masks shoreline, a painstaking task given the rugged and indented nature of the coast.

Every bay, inlet and rocky cove was examined for any sign of the missing men or their boat. The police were joined by local volunteers, some motivated by genuine concern, and others perhaps by the substantial rewards offered by the government and Lord Ardilaun for any information that led to a discovery.

The search soon moved from the shoreline to the water itself. The task of searching the vast expanse of the loch was, honestly, monumental. Loch Mask is not only large in area, but also incredibly deep in places, plunging to depths of over 180 feet.

To search this underwater realm, the authorities employed a range of methods. They used teams of men in boats to drag the loch bed with grappling hooks and heavy chains, hoping to snag the sunken boat, or grimly, the bodies of the victims. This was slow, gruelling, and often fruitless work, as the hooks frequently caught on the rocks and debris that littered the loch floor, leading to countless false alarms and dashed hopes.

As the days turned into weeks with no success, the search became more technologically advanced for the era. The authorities brought in a professional diver from England, equipped with the cumbersome and claustrophobic standard diving dress of the time, a heavy brass helmet, a canvas suit and weighted boots, all connected to the surface by an air hose. This diver, a man named Lambert, became a figure of morbid fascination as he descended into the black, freezing depths of the Loch, day after day.

The local people, many of whom had never seen such an apparatus, watched from the shore as he undertook his lonely and dangerous search in the silent world beneath the waves. Despite these extraordinary efforts, the Loch refused to give up its secrets. The dragging operations continued for weeks, covering square mile after square mile of the Loch bed. The diver made numerous descents into the murky darkness, but found nothing.

The complete absence of any clue was baffling and deeply frustrating for the searchers and the authorities. It also strengthened the theory of a carefully planned murder, as it suggested the perpetrators had gone to extreme lengths to conceal their crime. The search itself became a spectacle, a daily drama played out against the bleak winter landscape, watched by an anxious and divided public, all waiting for the discovery that they both dreaded and desperately wanted.

After more than three weeks of relentless searching, the breakthrough finally came, not from the sophisticated diver or the organized dragging parties, but from a more traditional method. On the 3rd of February a local man, working as part of the search, spotted something unusual in a shallow, secluded bay on the Lofts shore, not far from where the men had last been seen. It was a large canvas sack, partially submerged in the water, and weighed down with stones.

With a sense of dread, the searchers pulled the heavy bag from the water and opened it. Inside, they found the body of Joseph Huddy. He had been brutally murdered, his skull fractured by heavy blows. The Discovery Centre shockwave through the country, confirming the public's worst fears. This was no accident. It was a savage and premeditated crime. The focus of the search intensified, now with the certain knowledge that they were looking for more victims of a murder.

Just a few days later a second similar sack was found nearby. This one contained the body of the boatman, Michael Hines. He had met the same fate as Huddy, killed by extreme violence before being bundled into a sack and cast into the loft. The discovery of the two men's bodies in such a manner painted a horrifying picture of their final moments. The search now had one final heart-breaking objective, to find the body of ten-year-old John Huddy.

Despite the discovery of his grandfather, the search for the young boy proved tragically fruitless. The dragging continued. The diver descended again and again, but the loch held on to the boy's body. He was never found. This final, unresolved element of the tragedy added another layer of pain and mystery to the case. The thought of the small boy, lost forever in the cold, dark waters of the loch, was almost too much for the public to bear.

It transformed the crime from a brutal agrarian outrage into a deeply personal and poignant tragedy that touched the hearts of people far beyond the shores of Lochmask. The state of the bodies that were found told a clear story to the investigators.

They had been deliberately weighted down with stones, a clear attempt to ensure they would sink to the bottom and never be seen again. The fact that the sacks had been found in relatively shallow water suggested that the perpetrators had perhaps misjudged the currents or had been disturbed during their grim task. The boat, too, remained missing, presumed to have been scuttled and sunk in a deeper part of the loft.

The physical evidence was scant but damning. The authorities now had the bodies. What they needed were the killers. The focus of the investigation shifted from search and recovery to a full-blown murder inquiry.

With the confirmation of the murders, the Royal Irish Constabulary began a massive investigation. Their attention immediately focused on the small, isolated community on the western side of the loch, specifically the tenants whom Joseph Huddy had served with summonses on that fateful day.

The police believed the killers had to have come from this small group of men. They descended on the area in force, conducting house-to-house searches and interrogating the local residents. The atmosphere was one of intense fear and suspicion. The police were convinced of the locals' guilt, while the locals saw the police as an occupying force there to enforce the will of the landlord.

The investigation was hampered from the outset by a formidable wall of silence. The community, bound together by kinship, fear and a shared opposition to the landlord system, refused to cooperate. No one admitted to seeing or hearing anything unusual on the day of the disappearances. This silence was partly born of a deep-seated distrust of the authorities, and partly out of fear of reprisal from the perpetrators, who were believed to be members of a local secret society. To be an informer, or a tout,

was one of the worst things a person could be in rural Ireland at the time, often carrying a penalty of violence or even death. The police found themselves facing a community that had closed ranks completely. Frustrated by the lack of cooperation, the police resorted to making mass arrests. They arrested ten men from the area, including several members of the same family, the Casies, who were among the tenants Huddy had visited,

These men were taken into custody and subjected to intense interrogation. The authorities were desperate for a confession or for one of the men to break ranks and inform on the others. They used the promise of a pardon and a substantial financial reward to try and tempt one of the prisoners to turn Queen's evidence. This tactic placed immense pressure on the arrested men, forcing them to choose between loyalty to their community and their own survival. Eventually the pressure worked.

Two of the arrested men, Anthony and John Joyce, who were not related to each other, broke their silence. They offered to give evidence for the prosecution in exchange for their own freedom. Their testimonies would form the core of the case against the remaining prisoners. They claimed to have been part of the conspiracy and they painted a detailed and horrifying picture of the ambush and murder of the Huddies and Michael Hines,

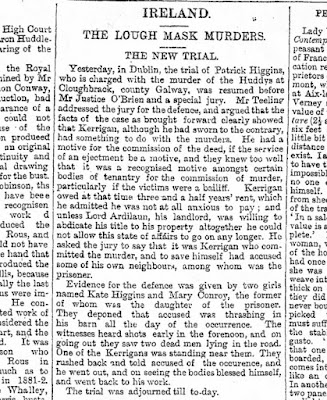

Their decision to become informers was a dramatic turning point in the case, but it also raised serious questions about the reliability of their evidence. Were they telling the truth, or were they simply saying what the authorities wanted to hear in order to save themselves? The trial of the Lochmask murder suspects began in Dublin in early 1883, and it captured the attention of the public across Ireland and Britain.

The case had become a symbol of the wider conflict in Ireland. For the government and the establishment it was an opportunity to demonstrate that law and order would be upheld and that agrarian crime would be punished severely. For the Irish nationalist movement it was seen as a show trial, an example of British justice being used to crush the spirit of the Irish tenantry.

The accused men, particularly Patrick Joyce and Patrick Casey, were presented as either brutal murderers or as martyrs of the land struggle, depending on which newspaper you read. The prosecution's case rested almost entirely on the testimony of the two informers, Anthony and John Joyce. They stood in the witness box and recounted a chilling story. They claimed that a group of local men, themselves included, had planned to attack Huddy.

They described how they ambushed the boat as it returned, dragging the men ashore and beating them to death with stones and oars. They detailed the grim process of putting the bodies into sacks, weighing them with stones and attempting to sink them along with the boat in the deep waters of the Loch.

Their testimony was graphic, detailed and damning, pointing the finger directly at their former neighbours who now sat in the dock. The defence lawyers, however, mounted a fierce challenge to the credibility of the informers. They argued that the informers were unreliable witnesses who had been coerced by the police and tempted by the promise of freedom and reward money.

They highlighted inconsistencies in their stories, and questioned why, if their account was true, the body of young John Huddy and the boat had never been found. The defence suggested that the informers had fabricated their stories to save their own skins, sacrificing innocent men in the process. They portrayed the accused as simple, Gaelic-speaking farmers who were caught up in a political storm they did not understand,

victims of a justice system that was biased against them from the start. Ultimately, the jury was persuaded by the informer's testimony. Three of the accused men, Patrick Joyce, Patrick Casey and Miles Joyce, were found guilty of murder and sentenced to death by hanging.

Two other men were sentenced to long terms of penal servitude. The verdict was met with cheers from the establishment, but with outrage from many in the nationalist community. A key point of contention was the conviction of Miles Joyce, who spoke only Irish, and whose pleas of innocence, translated through a court interpreter,

were allegedly not fully conveyed to the jury. His case in particular became a cause célibre, a symbol of the perceived injustice of the trial. The hangings were carried out, but the controversy and the questions surrounding the case refused to die.

The Loch mask murders left a long and dark shadow over the west of Ireland. The hangings did not bring closure. Instead, they deepened the sense of bitterness and injustice felt by many in the community. The fate of Miles Joyce, in particular, became a powerful symbol of wrongful conviction. It was widely believed that he was an innocent man, sacrificed by a system that needed convictions to quell the land war.

The story of his final moments on the scaffold, where he continued to protest his innocence in Irish, became a part of the folklore of the region. The belief in his innocence was so strong that it was said that the grass would never grow on his grave in the prison yard. For decades after the trial, the story was passed down through generations, not as a simple tale of crime and punishment, but as a complex story of political conflict, betrayal and injustice.

The figures of the informers, Anthony and John Joyce, were reviled, their names becoming synonymous with treachery. The men who were hanged, especially Miles Joyce, were remembered as martyrs. The story served as a potent reminder of the harsh realities of the land war and the deep divisions it had created within Irish society. It became a cautionary tale about the dangers of informing and the power of the state to crush dissent.

The mystery of what truly happened on that day in 1882 has never been fully resolved. While the court delivered its verdict, doubts have always remained. Was the account given by the informers the complete truth, or was it a version of events tailored to please the authorities? And the most poignant mystery of all, the fate of young John Huddy, remains unanswered.

His body was never recovered from the loft, a final, sorrowful, loose end in a story full of tragedy. His absence serves as a constant, silent testament to the horror of the event, a reminder of the innocent life caught up in the brutal conflict of adults.

Today the story of the Lough Masque murders is remembered as a significant and tragic episode in Irish history. It is more than just a local crime story, it is a window into one of the most turbulent periods in the country's past. It illustrates the immense pressures faced by ordinary people during the land war and the extreme lengths to which people were driven by poverty and a desire for justice.

The dark brooding waters of Lochmasc still hold their secrets, but the story of Joseph Huddy, his grandson John, and the men who were accused of their murder continues to be told, a sombre and enduring part of the historical landscape of Ireland.

Comments