.jpg)

In the complex and often shadowed history of the Troubles, few figures are as startlingly contradictory as Father Patrick Ryan. To some, he was a dedicated man of God, a priest who answered a higher calling. To others, particularly the British authorities, he was a dangerous terrorist, a key architect of the IRA’s bombing campaign. Known universally as The Padre, this Co Tipperary native lived a life that, honestly, just defied simple categorisation. His story is not merely one of a priest who strayed from his vows, but of a man who deliberately placed himself at the heart of a violent conflict, using his clerical collar as both a shield and a key to unlock doors that led to international arms deals and devastating acts of terror. The name Patrick Ryan became infamous in the late nineteen eighties, echoing through the corridors of power in London, Dublin, and Brussels. He was the subject of intense diplomatic rows and front-page headlines. Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher publicly labelled him a very dangerous man, a description he would later embrace with a chilling sense of pride. This was not a foot soldier or a low-level sympathiser. Ryan was a master strategist, a fundraiser, and a technical expert whose skills directly enabled some of the most notorious attacks carried out by the Provisional IRA. His journey from a missionary in Africa to the IRA's most valuable link with Muammar Gaddafi's Libya is a testament to his conviction and his capacity for clandestine operations that left an indelible scar on Anglo-Irish relations. Understanding The Padre requires looking beyond the sensational headlines that followed his every move. His life forces us to confront uncomfortable questions about faith, nationalism, and the justifications for political violence. Ryan’s narrative weaves together the piety of his religious background with the calculated logic of an urban guerrilla. He was a man who could celebrate Mass in the morning and, by his own admission, spend the afternoon devising new ways to kill brit Soldiers. He saw no conflict between his faith and his actions, viewing his role in the IRA as a righteous crusade against British oppression in the North of Ireland. His death in June two thousand twenty-five at the age of ninety-five did not settle the controversies surrounding his life; instead, it reignited them. For decades, he maintained a careful public silence, denying the more serious accusations levelled against him. But in his final years, he chose to speak out, providing candid, and often shocking, confessions about his deep involvement in the armed struggle. These revelations confirmed what his pursuers had long suspected and provided a final, defiant testament from a man who remained unrepentant to the end. The story of The Padre is a crucial, a chapter in the history of the Troubles, revealing the intricate global networks that sustained the conflict and the profound moral complexities at its core.

The Early Years

Born in Co Tipperary in nineteen thirty, Patrick Ryan’s early life followed a path familiar to many devout young Irishmen of his generation. He was drawn to the priesthood, a vocation that promised a life of service and spiritual purpose. He joined the Pallottine Order and was ordained in nineteen fifty-four, embarking on a career that, honestly, seemed destined for quiet devotion rather than global notoriety. His first significant posting was as a missionary in Tanzania, where he spent years working in communities, building schools, and tending to the spiritual needs of his parishioners. This period abroad shaped him, providing him with practical skills and a worldview that extended far beyond the shores of Ireland. It was a life of humble service, a stark contrast to the path he would later choose. The catalyst for his transformation came in nineteen sixty-nine, with the eruption of the Troubles in Northern Ireland. From his vantage point in Africa, and later from a new posting in the United States, Ryan watched the unfolding events with growing anger. The images of civil rights marchers being beaten, of Catholic communities under siege from loyalist mobs, and the deployment of British troops on the streets of Belfast and Derry ignited a fervent sense of Irish nationalism within him. He felt that the Catholic and nationalist population was being oppressed and that the British state was complicit. His religious conviction began to merge with a political one; he came to believe that standing by idly was a moral failure. This conviction soon translated into action. While based in America, he began using his position as a priest to raise funds. Initially, he claimed this money was for the families of nationalist victims, providing relief for those who had lost their homes or loved ones. However, his activities quickly evolved. He became a crucial link for the burgeoning Provisional IRA, using his clerical status to travel without suspicion and build a network of sympathisers and donors. His role was no longer just about charity; it was about actively supporting a paramilitary organisation dedicated to overthrowing the state through armed force. He was transitioning from a man of peace to an enabler of war. By the early nineteen seventies, Ryan had fully committed himself to the republican cause, a decision that would ultimately lead to his dismissal from the Pallottine Order in nineteen ninety. He had chosen a side, and he pursued his new mission with the same zeal he had once dedicated to his missionary work. He had chosen a side, and he pursued his new mission with the same zeal he had once dedicated to his missionary work. He saw the IRA’s campaign not as terrorism, but as a legitimate war of liberation against an occupying power. His background as a priest gave him a unique cover, allowing him to operate in the shadows, building the connections and securing the resources that would fuel the conflict for years to come. The missionary had found a new, more violent, calling.

.jpg)

Gaddafi’s Emissary

One of Father Patrick Ryan's most significant and destructive contributions to the IRA's campaign was his role as the chief architect of the relationship with Muammar Gaddafi's Libya. In the international landscape of the nineteen seventies and eighties, Gaddafi positioned himself as a sponsor of revolutionary movements worldwide, and the IRA was a natural beneficiary of his anti-Western stance. Ryan became the crucial middleman, the trusted envoy who could bridge the gap between the Irish paramilitary group and the North African state. His status as a priest provided him with unparalleled cover, allowing him to travel to Tripoli and other destinations for sensitive negotiations without attracting the attention that a known republican paramilitary figure would. He was, honestly, the perfect clandestine operator. The connection he forged was astonishingly fruitful for the IRA. Through his direct negotiations with the Libyan regime, Ryan facilitated the transfer of enormous quantities of weapons and money. This wasn't a trickle of support; it was a deluge that transformed the IRA's capabilities.

- hundreds of AK-forty-seven assault rifles, - machine guns,

- surface-to-air missiles, and, most critically,

- several tonnes of Semtex plastic explosive.

This high-grade military explosive became the IRA's signature weapon, used in many of its most devastating bombings. Ryan was not just a fundraiser; he was the quartermaster general for a re-energised and far more deadly organisation. Beyond the hardware, Ryan was instrumental in securing vast sums of money. He personally handled the transfer of what was reported to be over one million pounds from Libya to the IRA's war chest, though he later hinted that the true figure was far more millions.

- purchase equipment,

- support its full-time volunteers, and - run its complex network of safe houses and clandestine activities. Ryan’s trips to a bank in Switzerland, where he would collect suitcases filled with cash, became part of his legend. He was the financial lifeline that kept the armed struggle going, a role he performed with meticulous efficiency. The impact of the Libyan connection cannot be overstated. It professionalised the IRA's arsenal and allowed it to wage a prolonged, high-intensity campaign throughout the late nineteen eighties and into the nineteen nineties. The influx of Semtex, in particular, led to a new wave of bombings that were more powerful and harder to detect. Margaret Thatcher’s government was acutely aware of this threat, and stopping the flow of Libyan support became a top intelligence priority. At the centre of this international web of intrigue was The Padre, a priest from Tipperary who had become one of the most important figures in the IRA's global network of arms procurement.

Crafting the Tools of War

Father Patrick Ryan's value to the IRA extended far beyond his diplomatic and fundraising skills. He possessed a sharp, technical mind and a practical aptitude for engineering, which he applied directly to the mechanics of bomb-making. He was not merely a procurer of weapons; he was an innovator who helped refine the IRA's explosive devices, making them more reliable and deadly. His most significant contribution in this field was his work on bomb timers. In the early nineteen seventies, the IRA was struggling with unreliable timing mechanisms, which could lead to premature explosions or failures to detonate. Ryan identified a solution in a commercially available Swiss product- the Memo Park timer, a simple device designed to remind motorists when their parking meter was due to expire. Ryan realised that with some clever re-engineering, the Memo Park timer could be adapted into a highly effective and dependable long-delay timer for bombs. He travelled to Switzerland, buying up the devices in bulk and smuggling them back for the IRA's engineering department. He then applied his own technical knowledge to modify them, creating a timer that could be set for delays of many hours or even days. This innovation was a game-changer for the IRA. It allowed them to plant a bomb and be long gone from the area before it detonated, significantly reducing the risk to their own operatives and increasing the psychological terror of their campaign. The modified Memo Park timer became a hallmark of IRA bombs for over a decade. His expertise was not limited to timers. He was deeply involved in the overall design and strategy of the bombing campaign. He understood the science of explosives and provided technical advice on how to maximise their destructive potential. His knowledge of Semtex, the plastic explosive he had helped import from Libya, was particularly crucial. He advised IRA bomb-makers on how to use it effectively, ensuring that the devices they constructed were powerful enough to achieve their objectives, whether that was destroying a military target or causing massive damage in a British city. He was, in essence, a consultant for terror, applying his intellect to the grim science of killing. This technical role made him an exceptionally high-value target for the security services. While many people could raise money or smuggle weapons, few possessed Ryan's unique combination of skills. He was a priest, a diplomat, a fundraiser, and a bomb-making expert all rolled into one. His involvement went to the very heart of the IRA's operational capacity. He wasn't just helping to fund the war; he was actively designing the instruments of that war. This direct, hands-on involvement in the mechanics of violence is what separated him from many other sympathisers and cemented his reputation as one of the most dangerous men involved in the Troubles.

.jpg)

Hyde Park and Brighton

The technical innovations and vast resources that Father Patrick Ryan provided to the IRA were not abstract contributions; they had devastating real-world consequences. Two of the most infamous attacks of the era, the nineteen eighty-two Hyde Park bombing and the nineteen eighty-four Brighton hotel bombing, were directly enabled by his work. The Hyde Park bombing involved two separate devices. One, a nail bomb hidden in a car, exploded as soldiers of the Household Cavalry were passing, killing four of them and seven horses. The other bomb exploded under a bandstand in Regent's Park during a concert by the Royal Green Jackets, killing seven bandsmen. The long-delay timers used in these attacks were a product of the technology Ryan had helped to pioneer. Even more audacious was the attempt to assassinate the British Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher, and her entire cabinet at the Conservative Party conference in Brighton in nineteen eighty-four. An IRA bomb, fitted with a sophisticated long-delay timer, was planted in the Grand Hotel weeks before the conference began. It was a meticulously planned operation, designed to decapitate the British government in a single, catastrophic strike. The bomb detonated in the early hours of the morning, ripping through the hotel. It killed five people, including a sitting MP, Sir Anthony Berry, and seriously injured many others, including Norman Tebbit, a senior cabinet minister, and his wife Margaret. Thatcher herself narrowly escaped injury. For years, Ryan denied any direct role in these attacks, maintaining the fiction that he only raised money for humanitarian purposes. However, in a stunning admission for a two thousand nineteen BBC documentary, he finally confessed to his involvement. When the interviewer, Jennifer O'Leary, asked him if Margaret Thatcher was right to call him a man who had a hand in bombings, he gave a direct and unambiguous answer. I would say most of them, he replied calmly. One way or another, yes, I had a hand in most of them. Yes, she was right. This late-life confession confirmed what intelligence agencies had long asserted- that The Padre was at the operational heart of the IRA's mainland Britain campaign. His admissions laid bare the cold reality of his commitment. He was not a distant sympathiser but a key participant in plots designed to cause maximum carnage and political impact. The Brighton bombing, in particular, represented the pinnacle of the IRA's strategic ambition, an attack aimed at the very centre of the British state. That it came so close to succeeding was a testament to the effectiveness of the organisation's methods and technology. And behind that technology, providing the expertise and the resources, was Father Patrick Ryan, the priest who had dedicated his life to perfecting the art of destruction.

Arrest and Extradition Battles

As his importance to the IRA grew, so did the efforts of international law enforcement agencies to capture him. By the late nineteen eighties, Father Patrick Ryan was one of the most wanted men in Europe. The breakthrough for authorities came in June nineteen eighty-eight, when he was arrested in Belgium. A raid on his flat in Brussels uncovered a scene that confirmed his role as a senior IRA quartermaster. Police found large sums of money in various currencies, sophisticated bomb-making equipment, and traces of explosives. It was clear that he was running a significant IRA logistics and operational hub on the European mainland, far from the familiar battlegrounds of the North of Ireland and Britain. His arrest immediately triggered a major diplomatic crisis. The British government, led by a furious Margaret Thatcher, swiftly issued an extradition warrant, demanding that Ryan be sent to the UK to face trial for conspiracy to murder and causing explosions. The evidence against him was compelling, and Thatcher’s government was determined to see him brought to justice for his role in attacks like the Brighton bombing. For them, Ryan was not just another terrorist; he was a symbol of the IRA’s international reach and its cynical use of a clerical disguise to further its violent aims. The pressure on the Belgian government to comply was immense. However, the situation became incredibly complicated. Ryan, a seasoned operator, immediately went on a hunger strike in his Belgian prison cell, a tactic designed to garner sympathy and political pressure in Ireland. The case became a cause célèbre for republicans and their supporters, who argued that he could not receive a fair trial in Britain, a claim that resonated with some in the Irish political establishment. After months of legal and political wrangling, the Belgian authorities made a controversial decision. Instead of extraditing him to the UK, they put him on a military plane and repatriated him to the Republic of Ireland, effectively sidestepping the British request. This decision caused outrage in London. Margaret Thatcher was incandescent, publicly denouncing the Belgian government's actions and turning her full attention to pressuring Dublin. The British government immediately issued two new extradition warrants to the Irish authorities. However, the Attorney General of Ireland, John Murray, refused to execute them. He cited concerns that the intense media coverage and public comments from British politicians, including Thatcher herself, had created a situation where Ryan's right to a fair trial would be prejudiced. This refusal plunged Anglo-Irish relations to their lowest point in years, with The Padre at the very centre of the storm. He had escaped prosecution, but in doing so, had created a deep and bitter political rift between the three countries.

.jpg)

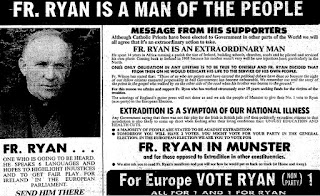

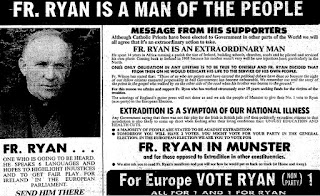

A Priest for Europe

Having successfully evaded extradition to the United Kingdom, Father Patrick Ryan returned to Ireland as a figure of both notoriety and, in some quarters, admiration. He was a free man, shielded by the Irish legal system from the charges awaiting him across the water. Seizing on his high public profile and the support he had garnered during the extradition battle, he made a surprising and unprecedented move. In nineteen eighty-nine, he announced his candidacy for the European Parliament elections, becoming the first Catholic priest to contest an election in the Republic of Ireland. He stood as an Independent candidate in the Munster constituency, a large electoral area that included his home county of Tipperary. His campaign was actively supported by Sinn Féin, the political wing of the IRA. For them, Ryan was a powerful symbol of resistance against Britain. His candidacy was a way to capitalise on the anti-extradition sentiment and to challenge the mainstream political parties on their stance towards the conflict in the North. Ryan ran on a platform of Irish sovereignty and opposition to British policy in the North of Ireland. His rallies attracted significant crowds, drawn by curiosity and a mixture of republican fervour and anti-establishment feeling. He was a charismatic and defiant figure, using his clerical status to lend an air of moral authority to his deeply political message. The electoral performance of The Padre was remarkable for an independent candidate with no political machine of his own. He polled impressively, securing over thirty thousand first-preference votes. While this was not enough to win one of the highly contested seats in the Munster constituency, it was a significant showing that sent a clear message to the political establishment in Dublin. It demonstrated that there was a substantial minority of the electorate who were sympathetic to his cause and deeply distrustful of the British justice system. His vote count was a public rebuke to the pressure that had been applied by London for his extradition. Although his foray into electoral politics was short-lived and he was not elected, it served its purpose. It allowed him to transition, in the public eye, from a shadowy fugitive to a legitimate political actor, at least for a time. The campaign kept his name in the headlines and reinforced the narrative that his was a political case, not a simple criminal one. For Father Patrick Ryan, the European election was another front in his lifelong war against the British state. He may have lost the election, but he had once again managed to challenge and embarrass the authorities in both London and Dublin, proving his ability to operate effectively in the political arena as well as in the shadows.

A Life Without Regret

For most of his life following the extradition controversy, Father Patrick Ryan maintained a public facade of denial. He would admit to raising funds for the families of prisoners and victims of the conflict, but he consistently and vehemently denied any involvement in the procurement of weapons or the planning of bombings. He cultivated the image of a humanitarian priest caught in the crossfire of a political conflict, wrongly accused by a vindictive British state. This narrative allowed him to live a relatively quiet life in Ireland, protected from prosecution and shielded by the ambiguity of his past. For decades, the full truth of his activities remained a matter of intelligence reports and speculation. This carefully constructed wall of silence came crashing down in his final years. In a series of extensive interviews for the two thousand nineteen BBC documentary Spotlight and my subsequent book, The Padre, Ryan chose to finally tell his story in his own words. The confessions he made were stunning, not only for their content but for the calm and matter-of-fact manner in which they were delivered. He admitted everything. He confirmed his role as the IRA’s link to Libya, he detailed his work on bomb timers, and he confessed to having a hand in most of the major bombings he was accused of, including the attacks in Hyde Park and Brighton. What was perhaps most shocking about his confessions was his complete and utter lack of remorse. When asked if he had any regrets about his life's work and the death and destruction it had caused, his response was chilling. I regret that I wasn’t even more effective, he stated, his voice steady. He expressed no sorrow for the victims, viewing them as unfortunate but necessary casualties in a just war. He saw his actions not as acts of terrorism but as legitimate acts of a revolutionary soldier. His Catholic faith, he argued, was not in conflict with his actions; rather, it underpinned his belief that he was fighting against a grave injustice. These late-life admissions provided a final, defiant flourish to his controversial story. They were the words of a man who remained, until the very end, a true believer in the cause to which he had dedicated his life. He wanted his role in the armed struggle to be known and recorded, not as a source of shame, but as a source of pride. By speaking out, he was not seeking forgiveness or understanding; he was making one last stand, ensuring that his version of history—the story of a priest who became a revolutionary and regretted nothing—was heard. His words stripped away any remaining ambiguity, leaving behind the stark and unsettling portrait of an unrepentant warrior.

.jpg)

The Padre's Final Chapter

Father Patrick Ryan passed away in a Dublin hospital on June fifteenth, two thousand twenty-five, at the age of ninety-five, following a short illness. His death closed the final chapter on one of the most contentious lives to emerge from the Troubles, but it did little to settle the debate over his legacy. Instead, it revived the intense media interest in his story. News of his death was met with sharply divided reactions, a reflection of the deep and lasting divisions created by the conflict itself. He remains a figure who is impossible to view through a single lens; his legacy is, and will likely always be, profoundly contested. For his supporters within Irish republicanism, The Padre is remembered as a hero, a patriot, and a dedicated revolutionary. They see him as a man of principle who was willing to sacrifice everything—his vocation, his freedom, and his reputation—for the cause of a united Ireland. In this view, his actions were not terrorism but legitimate resistance against a foreign occupying power.

My only regret? That I didn't do more for IRA

Father Patrick Ryan - A Patriot To Ireland

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Comments